By Ferdinand Omondi & Farouk Chothia

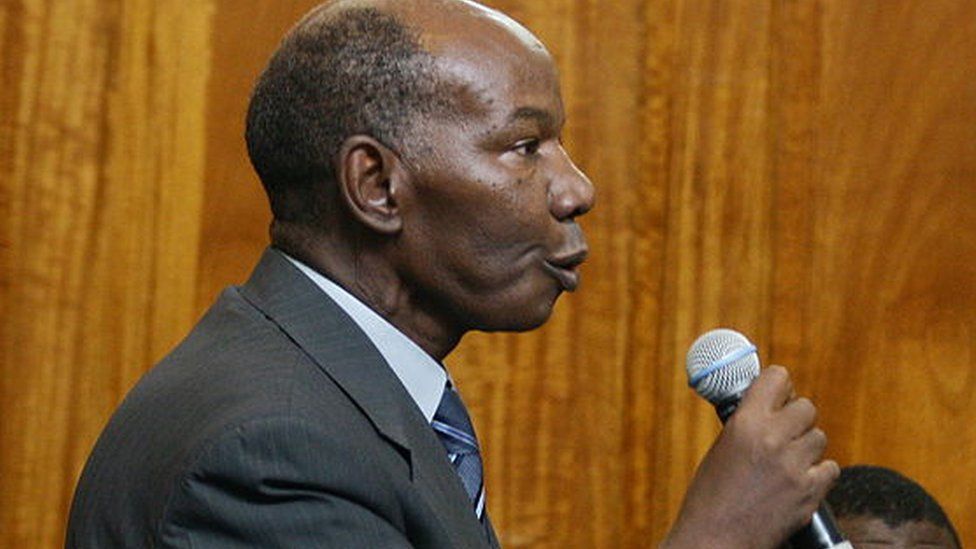

Appointed as Kenya’s first female chief justice in May 2021, Martha Koome has handed down the most important judgment in her short career as the nation’s most senior judge by upholding Deputy President William Ruto’s victory over Raila Odinga in the 9 August presidential election.

She gave her verdict in a calm, and some would say, understated manner, but her words were powerful – there was no “conspiracy” against Mr Odinga, and his legal team had failed to present a water-tight case to prove the result was rigged in favour of Mr Ruto.

The 62-year-old was appointed chief justice in May last year by outgoing President Uhuru Kenyatta after she came top of 10 candidates interviewed in front of a live television audience by Kenya’s Judicial Service Commission (JSC).

“This woman is a breath of fresh air. She answers questions the way they have been asked and actually puts her own professional stamp on them,” one person commented at the time about her performance.

During her interview she referenced her difficult experience growing up in Meru in rural eastern Kenya in a polygamous family – she was born in 1960, three years before the end of colonial rule.

“I am a villager in the truest sense. My parents were peasant farmers and we were 18 children from two mothers. So, for all of us, especially girls – it was a struggle to overcome the odds.”

And she overcame more odds to reach chief justice as she was not favourite, with pundits putting their money on Fred Ngatia to be the winning candidate as he had represented Mr Kenyatta in the dispute over the 2017 election.

The Supreme Court annulled Mr Kenyatta’s victory in that election, citing irregularities. A new vote was ordered, which Mr Kenyatta went on to win after Mr Odinga boycotted the re-run.

Mr Ngatia may not have won the president’s election case, but his fluency and elucidation of legal jurisprudence on the floor of the court at the time earned him top marks in the eyes of Kenyans across the divide.

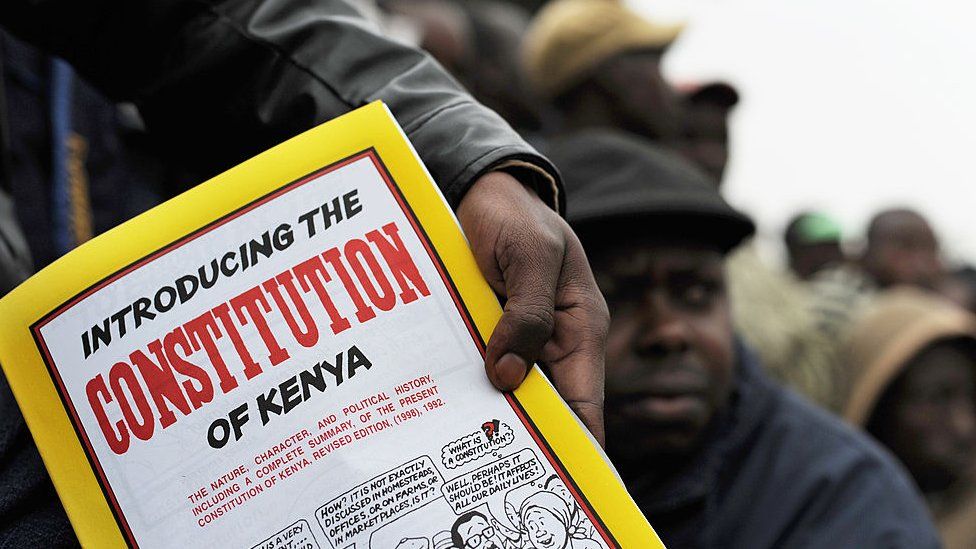

However Justice Koome was calm, confident and measured during her four-hour grilling – and her record on children and gender rights as well as her role in drafting Kenya’s 2010 constitution, in particular the Bill of Rights, stood out.

She spoke with pride about how the constitution now outlaws gender discrimination unlike the old one which “outrightly discriminated against women”.

“They could not confer citizenship, it allowed customary practices to prevail… such as child marriage, and FGM. We’ve come a long way,” she told the interview panel.

In 2020, Chief Justice Koome was a runner-up for the UN’s Kenya Person of the Year Award “for her advocacy of the rights of children in the justice system”.

She has also served as a commissioner on the African Union’s Committee on the Rights and Welfare of Children.

Married with three children, she has an impressive career spanning three decades after graduating in law from University of Nairobi in 1986 – and has earned various other degrees over the years.

She started as a legal associate in 1988, before forming her own law firm as managing partner in 1993. During her private practice, she became famous for her defence of human rights, representing political detainees during the regime of President Daniel arap Moi.

She was among the lawyers involved in the clamour in the 1980s to repeal Section 2A of the constitution which made the country a one-party state.

Often her colleagues would not want to represent female clients, so she took on their cases and came to see how difficult to it was to get justice for women in the courts when it came to property rights within marriage and inheritance as the law was “dominated by the patriarchy”.

This spurred her on to seek reforms to ensure the law “took care of families because families are the foundation of society”, Justice Koome said in her interview.

She became what she called “a firebrand” in her activism – and was a founding member of the Federation of Women Lawyers (Fida), which has since become synonymous with pro-bono representation of victims of gender and sexual violence in Kenya.

In 2003, the seasoned lawyer joined the bench when then-President Mwai Kibaki appointed her a High Court judge.

For the next eight years she headed the land and environmental courts as well as the family division in Nairobi.

She also served in satellite courts where she credited herself with clearing a massive backlog of cases at a pace she said had not been done before on the continent.

Promoted to the Court of Appeal in 2012, four years later she applied unsuccessfully to be a Supreme Court judge.

Her biggest challenge during her JSC interview was defending her part in an emergency Court of Appeal hearing on the eve of the election re-run in 2017.

A High Court judge had ruled on a case that day that all returning electoral officers and their deputies had been illegally appointed.

She and two other appellant judges overturned this, allowing the vote to go ahead – an interim order to avert a constitutional crisis, she said.

At issue for the interview panel was the fact that the ruling was made after official working hours and without all parties present – not the decision itself.

An unflustered Justice Koome explained that in extraordinary circumstances of national importance the appeal court could do so – and repeated several times that the Supreme Court had subsequently found there had been no problem with the returning officers and the suit had been null and void from the beginning.

Martha Koome is the 15th head of Kenya’s highest court since independence.

She once described herself as a good team player – and said she would not hesitate to pick up the phone to the president as chief justice to talk things through if need be.

This she believes is the best method for ending confrontation – helped by food.

When asked how she would deal with her fellow Supreme Court judges if there was friction, lunch was her solution.

“Food helps people talk nicely… so we will have a couple of retreats, eating [there] to understand what is the problem.”

Whether she had to take the six other judges for lunch when they deliberated on Mr Odinga’s petition is not known, but their ruling was unanimous.

That will only enhance the court’s – and the chief justice’s – credibility in the eyes of many Kenyans.